I had planned to travel after retiring from my long career in elementary education, and at age 63, I volunteered for the Peace Corps. One of a group of 30 education volunteers sent to Lesotho in 1993, I served as a resource teacher—essentially a teacher trainer and supervisor—in rural, mostly church-based primary schools, where the students ranged in age from 6 to 13, and occasionally older.

I suppose I experienced certain challenges because of my age. I never did learn the Sesotho language, for one. And I refused to ride a horse, as volunteers working in rural mountain locales were encouraged to do. I taught on a rotating basis at five different elementary schools, one of them a little mission school up in the mountains. I had to hike in along dusty, steep, and rocky trails that turned slick when it rained, and navigate a series of stepping-stones across a creek, with Doc Martens on my feet and a pack on my back. I’d spend the night on the mountain and hike out the next day. And I loved it. Everyone knew who I was because I was the only Peace Corps person around. When I walked to my schools, they would call out to greet me, “Mé Betty!”—Miss Betty!

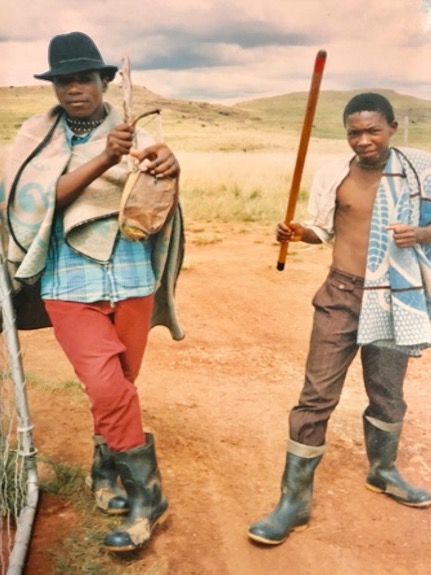

I would demonstrate classroom methods for the local teachers and hold workshops on how to teach different subjects, like English, sewing, art. The kids only had one book. It was all rote learning, all memorization. We were trying to help them branch out a little bit. But the primary schools mostly provided babysitting and hot lunch for the students. Lesotho’s rural schools were suffering as a result of the country’s weak economy; attending school was a privilege out of reach for many. Almost 50 percent of the nation’s workers were subsistence farmers or cattle herders, and a large portion of the male population migrated to work in South African mines. Teenage boys, who under other circumstances might have been my students, wandered the hillsides, wrapped in the ubiquitous multicolored Basotho blankets, herding sheep or goats or cows. I wanted to see these herd boys get an education, but there were no jobs. What was the incentive to go to school?

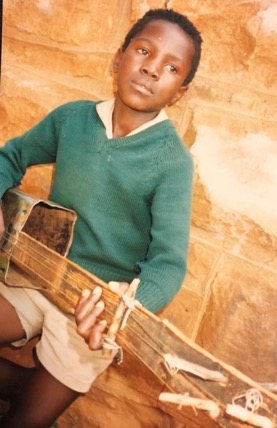

If the economy was poor, Lesotho has a rich heritage of music and dance. There was music at home, in the village, at school, at church—everywhere. The herd boys even had their own musical traditions to pass the time and calm their animals. As small children, the Basotho learn their people’s songs and dances. I loved their movements and their beautiful harmonies, and they would perform for me at the drop of a hat. The students would bring their instruments to school to practice and for show and tell. One boy played his instrument for me outside during recess. Another let me buy the instrument that he’d made. I was fascinated by their ingenuity and how they made things out of nothing—including soccer balls out of heated plastic bags.

One day while I was in the capital city of Maseru, wandering past the vendors who lined the streets, I noticed this little thumb piano, or mbira. I was fascinated by the handcraft—the body made from a gourd, with metal tines recycled from found objects and attached to the gourd to produce a range of tones. I bought it, this simple little instrument with a 3,000-year-old history in southern Africa. It was easy to hold, and even I could make pleasing sounds with it, though nothing like the masterful African musicians who blend its distinctive rhythms into their popular music, an echo from the past.

The music was a gift, something they could give to me. To have so little and to be so proud and positive—they didn’t want you to see the hard part. I’ve been back four times. My book club friends here have donated a lot of money for libraries and tuition. Now we’re supporting a soup kitchen that my friend is setting up in her village. I’ve helped her for many years since I got home. The relationships are my main memories. It’s been a big part of my life.